The Dominican Republic’s sun-soaked beaches and luxurious mansions provide the perfect backdrop for the gilded lifestyle of José Francisco Arata, the Venezuelan geologist turned oil magnate. While Arata enjoys the spoils of his severance package in one of the most exclusive Caribbean enclaves, former employees, shareholders, and contractors of Pacific Exploration and Production Corporation are left grappling with the financial wreckage caused by years of mismanagement and unchecked extravagance. The tale of Arata’s rise and fall is emblematic of the hubris and moral decay that have come to define the corporate elite in the oil industry.

A Marriage of Oil and Opulence

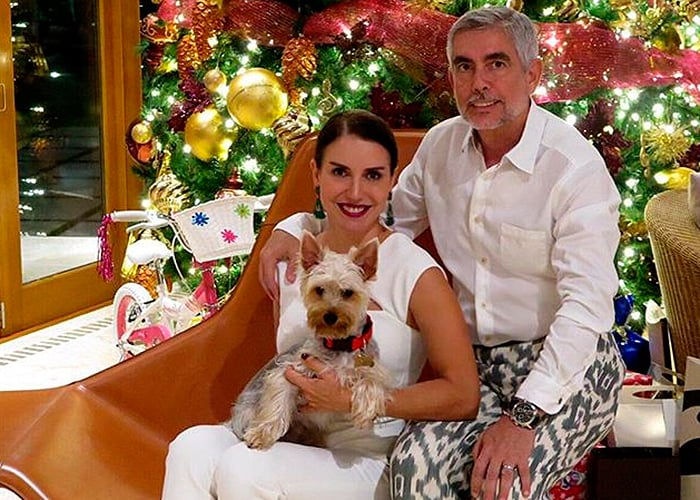

Arata’s lavish lifestyle reached new heights in April 2015, when he married Colombian actress Ana María Trujillo. The couple tied the knot in the Dominican Republic, where Arata’s family owns a sprawling 14-room mansion in Punta Cana. The wedding, a spectacle of excess, was attended by Colombian celebrities and corporate elites alike, with journalist Jorge Alfredo Vargas officiating as master of ceremonies. Following the ceremony, the newlyweds began their honeymoon in the same luxurious mansion, a prelude to their future residence in Casa de Campo, an enclave reserved for the ultra-wealthy.

The opulence of Arata’s personal life stands in stark contrast to the plight of Pacific Exploration’s stakeholders. Fired from his position as president of the company in August 2015, Arata walked away with a golden parachute worth $8.3 million. This severance package—a reward for nine years of questionable leadership—was paid even as Pacific Exploration was teetering on the brink of financial collapse. The company’s bankruptcy, which left countless employees and contractors unpaid, did little to dampen Arata’s appetite for luxury.

The Rise of Pacific Exploration: Promise and Exploitation

Pacific Exploration and Production Corporation was born in 2007 out of the ambition and desperation of former PDVSA executives like Ronald Patin and José Francisco Arata. The Venezuelans, victims of Hugo Chávez’s purges at the state-owned oil company, saw opportunity in Colombia’s underexploited oil fields. With financial backing secured from the Toronto Stock Exchange, the group—which included investment banker Serafino Iacono—launched Pacific Stratus Energy, later renamed Pacific Exploration.

The company’s success was meteoric. By capitalizing on Colombia’s favorable hydrocarbon laws and the pro-business policies of then-President Álvaro Uribe, Pacific Exploration rapidly expanded its operations. Fields like La Creciente in Sucre and Campo Rubiales in Meta became synonymous with the company’s meteoric rise, producing 25% of Colombia’s crude oil at its peak.

However, behind the glossy image of prosperity lay a darker reality. Allegations of labor exploitation and substandard working conditions began to surface as early as 2012. Contractors and workers reported precarious conditions and unpaid wages, but these warnings were ignored by the company’s leadership, who prioritized their personal enrichment over corporate responsibility. Arata, as president, bore significant responsibility for the culture of negligence and greed that ultimately led to the company’s downfall.

Ana Maria Trujillo herself published on her Instagram account her luxurious home in the exclusive Dominican golf course and beach

The Fall: Mismanagement and Manipulation

The cracks in Pacific Exploration’s foundation became impossible to ignore in 2015. The company’s stock plummeted amid mounting debts and falling oil prices. Yet Arata’s dismissal was not a consequence of financial mismanagement. Instead, it was the result of a power struggle among the company’s shareholders.

The so-called Bolichicos, a group of Venezuelan investors led by Alejandro Betancourt, sought to wrest control of Pacific Exploration. With 20% of the company’s shares in their hands, the Bolichicos torpedoed a proposed sale to the Mexican Alfa & Harbour Energy Group and demanded Arata’s removal. The board of directors ultimately acquiesced, paying a hefty price to rid themselves of the embattled executive. Arata’s $8.3 million severance package—negotiated in his original employment contract—was a bitter pill for the company’s creditors and stakeholders to swallow.

The wedding in Punta Cana was the anticipation of her arrival in the Dominican Republic, which would become her new homeland.

A New Life of Excess

While Pacific Exploration’s creditors scrambled to recover their losses, Arata began a new chapter of indulgence in the Dominican Republic. He and his wife, Ana María Trujillo, established themselves as fixtures of the island’s high society, investing in exclusive boutiques and building the Arata brand. Trujillo’s connections in the Colombian fashion and entertainment industries further cemented their status as Caribbean elites.

The Arata family’s escapades are emblematic of the moral vacuum left in the wake of Pacific Exploration’s collapse. While the company’s executives retreated to their luxurious hideaways, its former employees faced financial ruin. The once-thriving contractors and workers who powered Pacific’s rise were left to pick up the pieces, their grievances ignored by the very people who had profited from their labor.

The couple is committed to positioning the Arata brand

The Legacy of Pacific Exploration’s Executives

José Francisco Arata is not alone in his escape to opulence. Other Pacific Exploration executives have similarly leveraged their ill-gotten gains to build lives of luxury. Ronald Patin, for instance, purchased a $4 million mansion in Bogotá, while Serafino Iacono invested in a boutique hotel in Cartagena and a high-end restaurant in Bogotá. These men, who once touted themselves as saviors of Colombia’s oil industry, now reside in exclusive enclaves far removed from the fallout of their actions.

A Wake-Up Call for Accountability

The story of José Francisco Arata and Pacific Exploration is a cautionary tale of unchecked corporate greed. It is a stark reminder of the human cost of executive misconduct and the urgent need for accountability in the oil industry. For the thousands of workers and contractors left in financial limbo, the luxurious lifestyles of Arata and his peers are a bitter reminder of the injustice that pervades the corporate world.

As Arata continues to bask in the glow of his Caribbean retreat, the scars left by his tenure at Pacific Exploration remain unhealed. The company’s stakeholders, employees, and the broader Colombian public deserve more than empty apologies and superficial reforms. They deserve justice, transparency, and a commitment to preventing such egregious abuses of power in the future.

In the end, the high life of José Francisco Arata is not just a story of personal excess; it is a damning indictment of a system that rewards failure and punishes the most vulnerable. The sun may shine brightly on Arata’s Caribbean mansion, but the shadow of his actions will linger for years to come.